Learning CUDA: Workstation from Hell — Adventures with a Free GTX 1070

Posted on Sun 01 February 2026 in GPU, C/C++

Free Workstation? 🙋♂️ Count me in! I picked the free gaming workstation. Surprise twist—the HDMI output gave me no signal. Of course. The machine was a box of mysteries, but with an NVIDIA sticker on it, so I had a good hunch about the GPU.

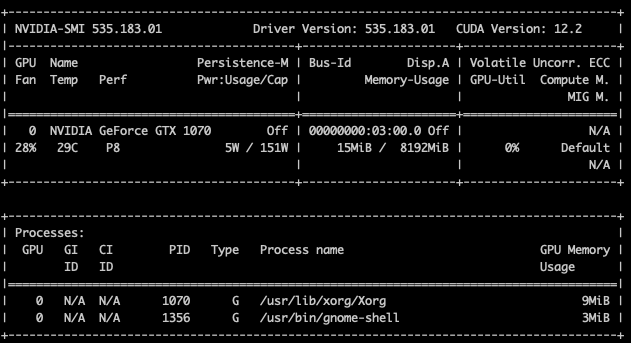

I wasn't trying to build an ML workstation—I'm saturated with models/GenAI at work and wanted something different: a hands-on, low-level tour of how GPUs actually work. I installed Ubuntu, SSH'd in, and started poking around. A quick

I wasn't trying to build an ML workstation—I'm saturated with models/GenAI at work and wanted something different: a hands-on, low-level tour of how GPUs actually work. I installed Ubuntu, SSH'd in, and started poking around. A quick nvidia-smi confirmed the headline act:

Yep: a NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1070. That’s a Pascal card from 2016—old enough to have earned its retirement benefits, young enough to be useful for tinkering.

Why this card is fine for me

The GTX 1070 has 1920 CUDA cores, modern cards double or quadruple that, but for my experiments in CUDA and for writing small numerical kernels, 1070-level parallelism will be more than adequate.

Imagine interns in corporate headquarters, this is the analogy I will use to talk about my GTX specs later on. See below

Imagine interns in corporate headquarters, this is the analogy I will use to talk about my GTX specs later on. See below

Memory and bandwidth — the boring but important bit

It comes with 8 GB of GDDR5 VRAM and about 256 GB/s memory bandwidth. I will tell what they are on later. But for now, it is not enough to host a large LLM, but perfectly fine for my smaller compute experiments, numerical kernels, physics hacks, and generally making the GPU sweat in reasonable doses.

GDDR5 is old-school compared to the newer GDDR7 used in recent cards. Think of it like SATA vs NVMe: still works, just slower.

Compute power — FLOPS you can brag about

Single-precision (FP32) throughput for the 1070 sits around 6.5 TFLOPS. This is how many floating point operations per sec it can do. Newer mid-range cards push much higher (19 TFLOPS and up), but raw TFLOPS aren’t everything — memory bandwidth, latency, and how I map a problem to threads mattere more I think while writing efficient kernels.

Tensor cores? Not here — and that’s a feature, not a bug

The GTX 1070 has no Tensor Cores. That means no magical mixed-precision matrix multiply shortcuts—just good old CUDA cores and manual thinking about memory accesses and parallelism. Since I'm learning the fundamentals, this has been the purest playground.

The workstation from hell (a short, tragic saga)

I was very happy that the workstation set up the stage with high-end specs on paper. It was built around the Intel i7-3930K (a 6-core/12-thread beast) seated in an Asus P9X79 Pro motherboard

This setup utilized the Intel X79 Express chipset, designed specifically for enthusiast-grade performance of its time. I had 32 GB of DDR3-1600 RAM installed across its eight physical slots, and for parallel processing. However, due to tight space clearance issues within the chassis (see the picture above), the GPU couldn't fit in the primary slot; It was seated in a secondary position that downgraded the connection to PCIe 2.0, even though the hardware was capable of PCIe 3.0.

Despite those specs, the machine was "Drama Central" from day one. The first red flag was the memory: out of the 32 GB installed, only 24 GB was ever detected. The Asus P9X79 Pro is notorious for being finicky with memory, and mine was clearly sick.

My back-of-the-envelope calculations for CPU <--> RAM bandwidth never matched the sluggish reality I saw during profiling. On paper, DDR3-1600 in a Quad-Channel configuration should be a monster.

The math is simple: \(1600 \text{ MT/s} \times 8 \text{ bytes (64-bit)} \times 4 \text{ channels} = \mathbf{51.2 \text{ GB/s theoretical peak}}\)

Accounting for standard overhead, I should have been seeing at least 40 GB/s. Instead, a deep dive with dmidecode revealed a Partition Width of 1. My conclusion (not sure) was the system had retreated into a Single-Channel (64-bit) mode, capping my throughput at a hard 12.8 GB/s ceiling. This explains why my C++ code actually slowed down when I added threads; 12 logical cores were fighting for a single 64-bit "lane," creating massive bus contention that dropped my real-world speeds to a pathetic 8 GB/s.

I spent weeks limping along on crippled bandwidth, wrestling with the 'usual suspects' of C/C++ masochism. We’re talking about the full, painful syntax experience: References, Pointers, and Pointer-to-Pointers—essentially maps to maps that might lead to data if the memory gods are feeling merciful. Despite the constant threat of a Segmentation Fault ruining my life, I’ve finally hammered out a solid block of CUDA code.

Then the thing i never imagined happened, the CPU water cooler pump failed suddenly, leading to a very hot, very sudden meltdown. Even before the water pump failed, the sound of the water moving around was annoying enough!. That was the final straw. I did the only thing any reasonable person would do: out of frustration, I tore the PC apart, salvaged the useful bits, and chucked the chassis and motherboard into the trash can 🗑️. Because I was so deep in the "zone" of writing code, most of my recent work wasn't committed to Git—a lesson learned the hard way.

The disk is still hiding those lost artifacts somewhere; I’ll deal with that disaster movie later. For now, the "workstation from hell" drama is officially closed.

Side quest: I got my hands on a NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin. Loved learning about unified memory and the embedded developer experience, but getting neovim to work on Jetson meant updating the jetpack. I dont want to go that rabbit hole for now and focus on learning cuda. So I shelved it for now — but more articles on Jetson to follow later.

Moving the GPU and a much nicer dev loop

I moved the GTX 1070 to an older Windows box (WSL + drivers) and for my surprise everything worked. I grumbled about Windows, but tooling has come a long way. The workflow felt sane again: Neovim + clangd + fast rebuilds, and I could iterate on CUDA code locally without the awkward remote edit/compile cycle. The only thing i am having hard time getting used to is the windows keyboard shortcuts (a daily Mac user would understand my pain!)

Using some powershell commands and simple C/C++/CUDA programs, I was able to know more about my rig.

RAM details

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

I have 32GB RAM running 1600MhZ (not overclocked or underclocked)

#!python

❯ powershell.exe -Command "Get-CimInstance Win32_PhysicalMemory | Select-Object SMBIOSMemoryType, Speed"

SMBIOSMemoryType Speed

24 1600

24 1600

24 1600

24 1600

Memory type of 24 indicates that I have DDR3 RAM,

CPU details

#!python

❯ bin/00_know_my_gpu

CPU Info

CPU Logical Cores: 8

CPU model name : Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-3770K CPU @ 3.50GHz

Physical Cores: 4

-----------------------------------

I have 4 cores or 8 logical cores running approximately at 3.5GHz (could have been overclocked). I think i7-3770k was a very good processor.

GPU details

Now lets get the actual business of this blog article by inspecting the GPU properties.

#!python

--- Device 0: NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1070 ---

Compute Capability: 6.1

Multiprocessors (SMs): 15

Total CUDA Cores: 1920

Max Threads per SM: 2048

Registers per SM: 65536

Registers per Block: 65536

Shared Memory per SM: 96 KB

Shared Memory / Block: 48 KB

Total Global Memory: 8191 MB

Memory Bus Width: 256 bits

Memory Clock Rate: 4004 MHz

Warp Size: 32 threads

L2 Cache Size: 2048 KB

Intern Analogy

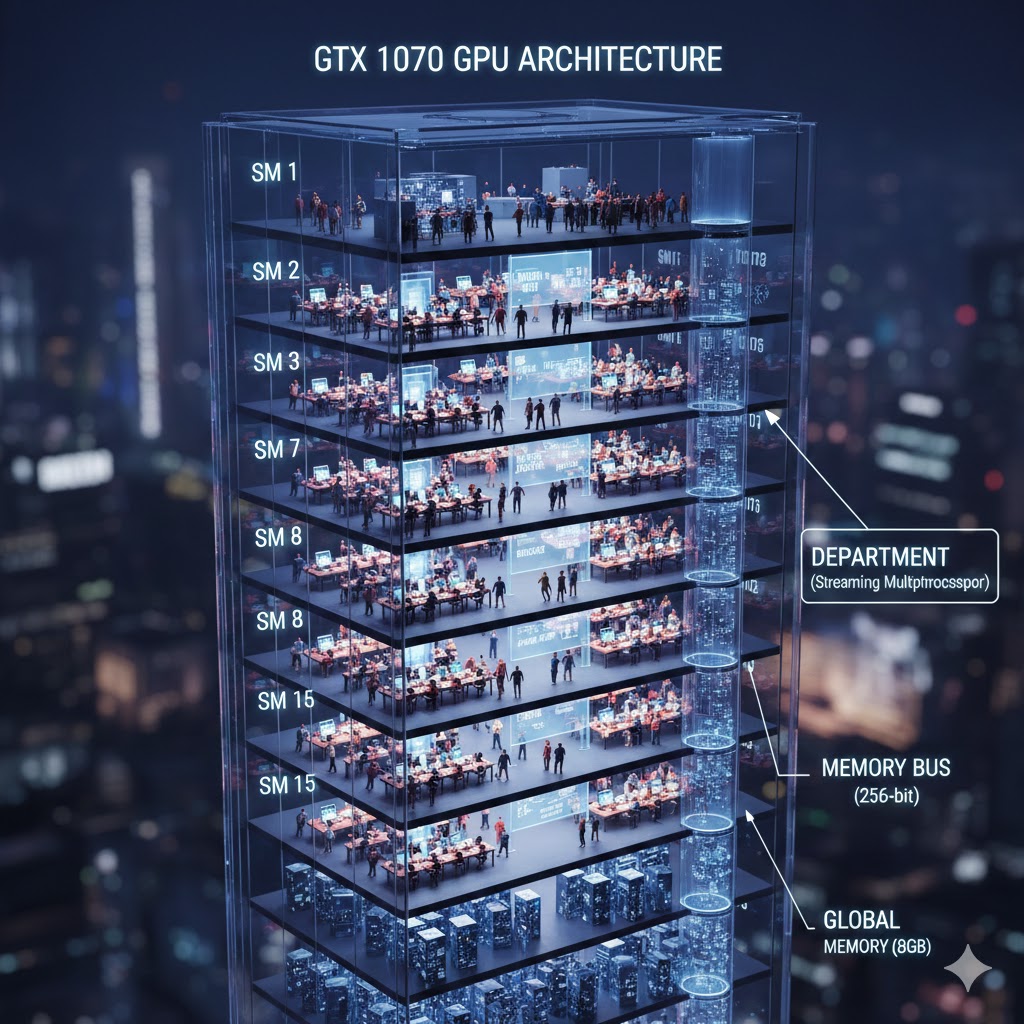

To understand these specs, I like to imagine my GTX 1070 not as a circuit board, but a massive, highly disciplined corporate headquarters.

Multiprocessors (15 SMs): The Departments, The building is divided into 15 distinct floors or departments. Each department is self-contained and handles its own workload.

Total CUDA Cores (1920): The Calculators Across the entire building, there are 1,920 high-speed calculators. Each department (SM) gets 128 calculators to share among its staff.

Max Threads per SM (2048): The Fire Code This is the maximum number of Interns allowed on a single floor at one time. Even though there are only 128 calculators, we keep up to 2,048 interns in the room. Why? So that the moment one intern stops to wait for data, another is ready to grab their calculator and keep working.

Warp Size (32): The Team Shift Interns never work alone; they work in synchronized teams of 32. When the manager says "Calculate," all 32 interns in a Warp punch their numbers into 32 calculators at the exact same microsecond. It’s perfect harmony.

Registers (64K per SM): The Desk Space Registers are like the actual surface area of an intern's desk. It's where they keep the numbers they are working on right now. If the interns have to do "heavy math" with lots of variables, they need more desk space, which might mean we can fit fewer interns on the floor.

Shared Memory (96 KB per SM): The Department Whiteboard This is a small, incredibly fast whiteboard at the front of the room. All interns on that floor can see it and share notes on it. It’s much faster than walking all the way to the "Basement" (Global Memory) to look something up.

Total Global Memory (8 GB): The Basement Warehouse This is the massive storage area for the entire building. It holds all the data, but it’s far away. If an intern has to go here to get a piece of paper, it takes them a "long time" (in computer cycles), which is why we try to keep as much as possible on the Whiteboards or the Desks.

Memory Bus Width (256 bits): The Elevator Capacity This determines how much data can be moved from the Warehouse to the Departments at once. A 256-bit bus is like having a large, wide elevator that can move many boxes of data simultaneously.

Memory transfer rate between CPU and RAM

coming soon.

Memory transfer rate between RAM and VRAM (host-device transfers)

coming soon.

Memory transfer rate between RAM and VRAM (host-device transfers)

coming soon.